Filters not buckets: How to prioritize your internal products

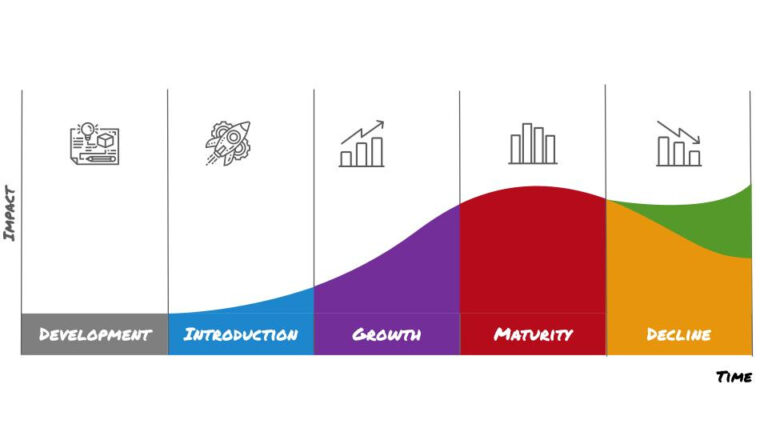

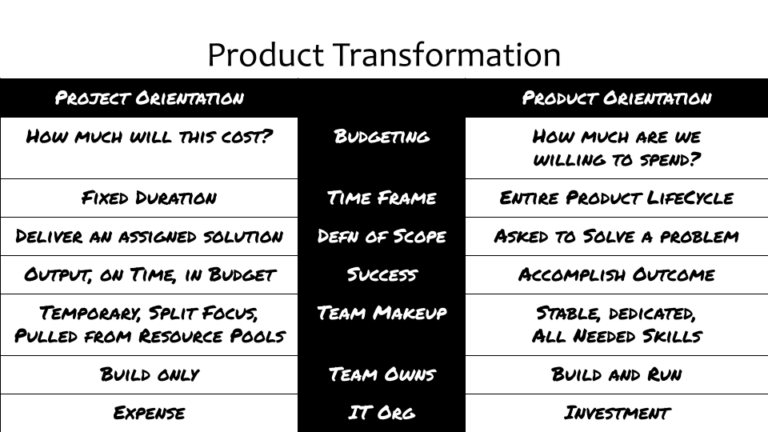

I had the opportunity to speak at Agile + DevOpsDays Des Moines today where I delivered Filters not Buckets, prioritization for product people. In the presentation I described a set of prioritization principles and described how to approach prioritization at different stages of the Internal Product Lifecycle. You can get the details from the presentation page on insideproduct.co.is the main bit about p

At the end of the session, the audience asked a few great questions that I wanted to share.

Prioritization vs Sequencing

One of the prioritization principles I shared was that prioritization ≠ sequencing. One attendee asked me to explain the significance of that a little more.

So a quick diversion into definitions:

-

Prioritization = deciding what to do and not do

-

Sequencing = deciding what order you’re going to do the things you decided to do.

Given the tendency to bucket that I describe below, most organizations have come to believe that prioritization means putting things in order, without removing anything to start with.

It’s helpful to think of prioritization and sequencing as different so that you remember to do them both.

First, prioritize your initiatives and remove those you aren’t going to do. Second, sequence those that you kept.

How do you make saying “no” easier?

This is a paraphrase of a couple questions, and my answer requires a little bit of a back story.

I got the got the phrase filters not buckets from my friend and co author Todd Little. He observed that you should use your strategy as a filter, not a set of buckets. This speaks to the tendency of organizations when they’re pitching their pet projects to try and explain how that project fits into several different buckets. The thought being the more buckets it fits into, the more likely it is to get approved.

Unfortunately, just because something gets approved, doesn’t mean it’s going to get done. When people justify their idea by associating it with multiple buckets, nothing actually gets filtered out. As a result, the teams that have the honor of building the things on this wish list find themselves faced with an impossible to complete backlog at the beginning of the year.

So they don’t complete it.

Why does this happen? There is a vicious cycle where IT departments have trained their friends in the other departments (let’s call them stakeholders) to act like bad customers.

During planning at the end of the previous year, IT leaders are afraid of what would happen if they told their counter parts “no” at the beginning of the year. Ironically, IT doesn’t seem to have an issue saying “no” the rest of the year because their plate is already over flowing.

As a result, stakeholders have been trained by experience to submit everything during planning time that they think they may possibly want throughout the year. They then make absurd claims that their initiative addresses every single organizational priority. Stakeholders do this because they know that not everything will get done, so they want their initiative(s) at the top of the list.

This vicious cycle makes the fourth quarter of the year quite nerve wracking. For everybody. Stakeholders are trying to get their initiatives to the top of next year’s list, while suddenly finding out this year’s top of the list things aren’t going to happen.

I said all that to say this.

The way to avoid this vicious cycle is to say “no” early and often. But you want to say “no” in a way that doesn’t ruin your working relationships with your peers.

If you’re in IT and face the opportunity to say no, you want to make sure there’s a shared understanding about the criteria you’re going to use to make the decision.

You want to make sure your stakeholders know, and agree with, your decision filter.

Before you have to make the decision.

So at the start of planning discussions, before you talk about any initiatives, make sure everyone understands, and agrees with, the impact you’re seeking to drive. And also realize you’re going to use that impact to make decisions.

An example:

Let’s say the impact you want to drive is increase the number of users on your platform by 15% by the end of the next year.

Your decision filter is then: Will this initiative help us increase the number of users on our platform.

-

If the answer is yes, you continue considering that initiative in your planning discussions.

-

If the answer is no, you don’t.

Then, actually use that decision filter. If your stakeholders complain, you can remind them that they agreed to use that decision filter.

It may take a little bit of time to adjust to the new practices of facing reality, but everyone will appreciate it in the long run.

What about when your org doesn’t have a single priority?

I’m not sure when priority became plural. Most of the attendees agreed with me, and as one attendee pointed out “most organizations do have multiple priorities.”

Yes, yes they do.

So if you’re trying to use priority as a decision filter, what do you do when there are multiple priorities? How do you decide which one to use for your filter?

Ideally, you try to get the organization to actually identify a specific priority.

Failing that, determine which one priority (objective, goal, etc) is most relevant for the nature of your product. In fact, this is the first, key decision you should make.

This is probably best explained by an example.

When I was at a wholesale distributor, I was working on an internal product that the distributor provided to its customers to help them maintain their inventory. The thought was if the customers used that tool it would make them easier to keep track of their inventory of the company’s products and order more when they run low.

This organization also had a set of key strategic priorities. I can’t remember all of them, but some were:

-

Fix supply chain

-

Retain out best customers

-

Some good corporatey sounding objective*

-

Another ambitious organizational goal*

These are paraphrases, some more so than others.

Which strategic priority do you think was most relevant for the inventory management platform.

That’s right, it was a retention play. So our decision filter became, in effect, “Will this help us retain our best customers?”

Are all frameworks bad?

This one was perhaps my favorite question. “These days it seems to be the thing to do to bad mouth all frameworks. Are you saying that all frameworks are bad?”

I’m guilty of bad mouthing frameworks. But that doesn’t mean I think all frameworks are bad.

Prioritization frameworks that try to make the subjective look objective are bad.

But not all frameworks are bad. But good frameworks applied badly are bad.

What does “applied badly” mean – when you apply a framework and lose site of why you implemented the framework in the first place.

A couple of examples of that:

-

organizations that adopt agile to…”be agile”

-

organizations that are adopting a product operating model because some well known thought leader told them to.

Frameworks can be very helpful, but they lose their usefulness if you forget why (or never knew why) you adopted them in the first place. When that happens, you become more focused on implementing the framework “the right way” and can’t tell if it’s actually helping you.

Thanks for reading

Thanks again for reading InsideProduct.

If you have any comments or questions about the newsletter, or there’s anything you’d like me to cover, let me know.

Talk to you next time,

Kent