How should you document testing issues?

Here’s a description of how a team I worked with approached testing and dealing with test issues, as well as an explanation as to why we approach testing in this fashion.

As a starting point, it’s helpful to establish what outcomes you should expect from testing.

Why Test?

That may seem like a silly question that has an obvious answer.

Quite the contrary, I’ve run into more teams than I care to count who do a particular software development activity without a clear understanding of why they are doing that particular activity.

You shouldn’t treat testing as an activity that can only happen after development is finished.

As W. Edwards Deming explained in Out of the Crisis

Inspection does not improve the quality, nor guarantee quality. Inspection is too late. The quality, good or bad, is already in the product. As Harold F. Dodge said, ‘You can not inspect quality into a product.’”

You incorporate testing into your development process so that you can identify any potential issues, verify whether your addressing the issues you identified, and uncover any issues that you couldn’t identify until you build something and start using it.

How we approached testing

Here’s how a team I worked with recently approached testing in order to achieve the above outcomes.

It was a dedicated, stable, cross-functional team

The team included developers, a QA person, a UX person, and a product person. There wass no concept of a separate development team and a QA team. We were on the same team with a shared purpose. This reduced the distance between development and QA and maked it easier to incorporate QA throughout the entire development process.

Everyone owned testing

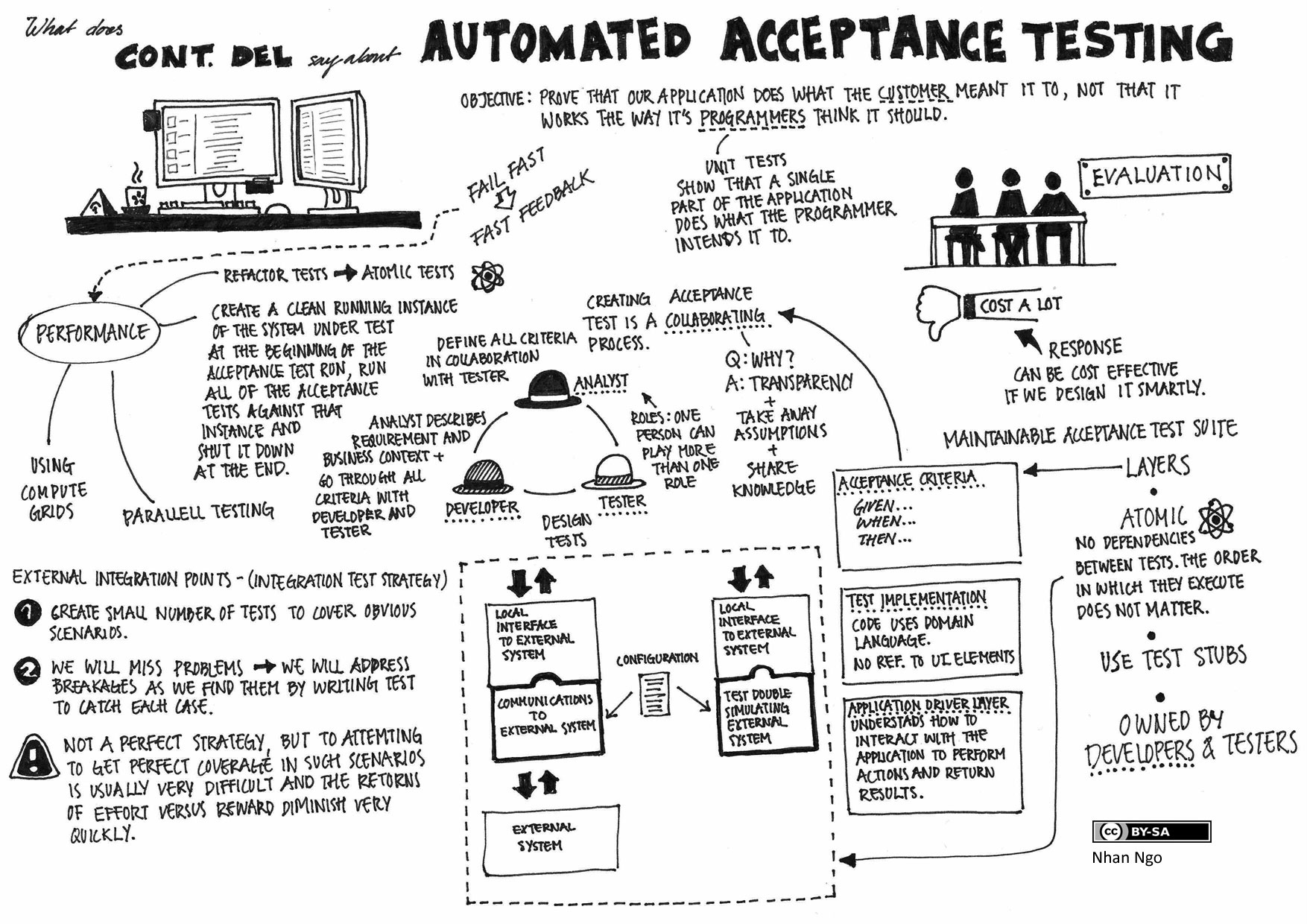

The team practiced Test-Driven Development and developers create automated unit and acceptance tests as part of their development efforts.

We used different kinds of tests to their strengths

We used the testing pyramid as a guide to what kind of tests we use for specific purposes.

We have many low-level unit tests, our acceptance tests exercise a service level, (avoiding the brittleness that comes with testing via the UI) and we have a small number of end to end automated UI tests. We supplement the automated tests with manual testing that focuses on the UI and exploratory testing. We also automate key end to end test scenarios to act as a regression test suite.

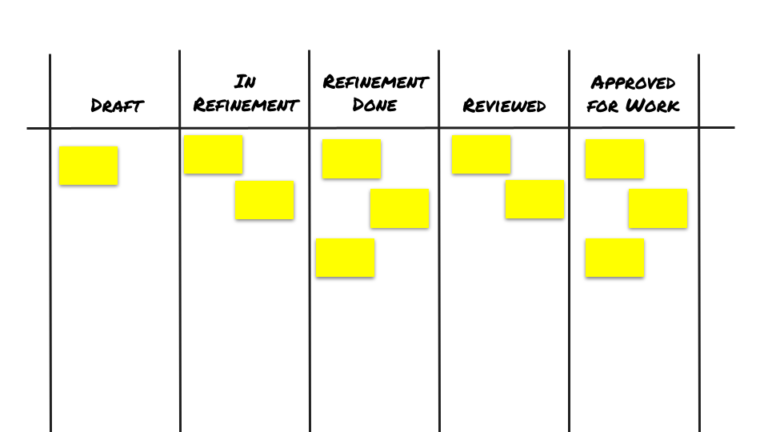

Testing was included in the definition of done

The team established the following definition of done, where these items need to be true in order for a backlog item to be considered done in a sprint:

-

Acceptance criteria met

-

All tasks completed

-

API Documented via Swagger (manually where necessary)

-

Adheres to code standards

-

All Continuous Integration builds complete including:

-

Unit tests passed on frontend and backend code

-

API acceptance tests passed

-

Unit tests passed on frontend and backend code

-

API acceptance tests passed

-

Code deployed to DEV environment

-

Code deployed to TEST environment

-

Manual tests on TEST environment pass

-

Meets any global Non Functional Requirements not listed in Acceptance Criteria

-

Product Owner Reviewed

The point about Manual tests on TEST environment pass is key when it comes to the discussion of handling issues identified during testing.

Any manual testing that is done on a product backlog item is done in order to consider it “done.” That means that testing is incorporated into the development process rather than considered a separate activity.

Resolving issues found during manual testing is a team sport

If manual testing found an issue with the backlog item, the person doing the QA let the pair who developed it know what they found (usually verbally and by a comment on the backlog item, or both).

The developer and QA generally had a conversation about the issue to determine if it was something that needed to be fixed in the code, whether it was a misunderstanding about the backlog item, or it was something outside the scope of the backlog item.

If the issue resulted in a code change, the developer(s) made the appropriate revision and let the QA person know when it was ready to retest. The backlog item wasn’t considered complete until the manual tests passed following the fix. If we created any documentation for the issue, we did it to communicate that something happened and to spark a discussion.

So did you not log bugs at all?

Of course we logged bugs.

It’s important to know what we mean when we said “bug”. To help with clarity we used different terms for different types of issues:

Types of Issues

Defect

A flaw found while testing a backlog item that prevents the backlog item from being called done.

How to address:

-

Fix immediately during the sprint before the associated backlog item is considered done.

-

Minimal documentation (note as a comment in the related backlog item)

In other words: if an issue is found before the backlog item is closed (defect), fix it.

Bug

An issue introduced by recent development and missed in testing (i.e. not found before the backlog item was marked done) or a flaw found in production that prevents software from functioning.

How to address:

-

Document as a Bug in our backlog tool

-

Diagnose, find solution

-

Prioritize

-

Pull into sprints based on priority

-

Perform Root Cause Analysis

-

Address the root cause through quality, communication, technology, automation, process improvements

In other words: if we found an issue after we called a backlog item done (bug), document it as a Bug and slot it into an upcoming sprint to fix.

Why document bugs and defects differently?

I know what you may be thinking… a flaw is a flaw why get (potentially) pedantic about calling them two different things and treating them differently?

They occur at different points in the development process and hence are best addressed in different ways.

To understand this fully, it’s helpful to consider the reasons why you may want to document bugs/defects and explore how each reason relates to bugs versus defects.

To capture the specifics about an issue

This is the main reason to record a defect or a bug.

When someone who didn’t create the code finds an issue, it’s always helpful to provide as much explanation about the issue as possible so that it’s easier to recreate, determine the cause, and fix.

There are differences in lag time between when you identify and fix a defect and when you identify and fix a bug.

You intend to address defects immediately, so you don’t want to spend a lot of time documenting the issue and tracking it separately from the backlog item. It’s best to document it directly in the backlog item and keep all that information in context.

When you run across an issue after the backlog item is already done, you may or may not address it immediately. You need to note information about the issue so that you can remember the specifics.

Since you’ve already closed the original backlog item, it’s often easier to create a new backlog item specifically for the issue. That’s where the bug backlog item type comes into play.

To remember to fix the issue

Another key reason you document an issue to act as a reminder to actually fix it. This becomes increasingly important the longer the lag between when you discover the issue and when you actually address it.

Defects are rather straightforward. You plan to fix it now. There’s no point in creating a separate item to track it, you can just note it in the backlog item that it relates to. After all, you’re not going to close that backlog item until it’s resolved.

Some bugs you’re going to fix right away. Other bugs you’re going to put off until later. It’s helpful to have a separate item to address that bug.

This is both to remind you to fix it and to explicitly schedule when you want to address it.

So teams can find stuff later on

You may want to document defects/bugs as a form of reference to help root cause problems that occur later on.

The idea is that if a problem occurs, the team supporting the product at the time can search through backlog items identified as bugs to find possible root causes. This assumes that all issues are recorded as a special type of backlog item.

There are some problems with this line of thinking. Backlog items – whether backlog items covering new functionality or bugs – are great at showing what changes occurred when.

They are not well suited for research across the entire product. They are project documentation.

If you’re trying to figure out what’s causing an issue in a product, searching through a bunch of bugs can be time-consuming and not very fruitful.

You’d be better off having system documentation that provides an overall guide to your product and helps direct the people trying to address the issue to the proper part of the product.

With that in mind, future research to help root cause new problems is probably not a compelling reason to document bugs or defects.

Tracking and traceability

You may want to document defects and bugs for “Tracking and traceability” purposes. In other words, it can be helpful to know if defects or bugs were found and whether they’ve been addressed.

There is value in knowing whether any defects or bugs have been found and when they were addressed. For defects, this is covered by the definition of done for backlog items. If there were defects found, they were addressed by the fact that the backlog item is done.

For bugs, this is covered by the creation of a separate bug backlog item.

It’s also helpful to know if there are any bugs that have not been addressed. You can tell this because the bug backlog items themselves are still open.

As mentioned before, you don’t need to track defects separately to determine if there are any defects still open – the related backlog items themselves would not be marked done if they have any unresolved defects.

The problem comes when “tracking” becomes a means of monitoring a team by those outside a team

If a team feels that their bugs are being monitored, those bugs and defects stop to lose their effectiveness as tools for the team. The team becomes wary about documenting bugs and long discussions (some of which turn into arguments) ensue about whether something is a defect or a bug or just an unrealized feature.

Discussions about how to address defects and bugs are healthy. Discussions about whether something is a defect, bug or neither is not productive.

The situation becomes worse when bugs become measures of performance for QAs. Everything a QA notices that doesn’t exactly meet their specific interpretation of the acceptance criteria will become a bug.

This condition results in a swirl as team members have to investigate every issue and it increases the number and intensity of discussions/arguments whether particular things are bugs or not. This creates an adversarial relationship between the team members. Developers think that QA are out to get them, and QA think their job is to catch developers making mistakes.

Tracking to know what items are left unresolved (ie via bugs) is helpful.

Tracking to pinpoint specific people who are introducing issues or documenting issues for the purpose of performance assessment leads to many undesirable unintended consequences. What small value may be gained from this exercise does not outweigh the negative impact of those consequences or the extra work required to document defects separately.

Documentation with a purpose

Documentation is not bad, as long as you understand what problem you’re trying to solve and use the proper format to solve that problem.

Documenting defects inside the related backlog item achieves the purpose of documenting the defect – to remember the specifics of that defect. This approach reinforces the cross-functional nature of the team and keeps everyone focused on building quality into the product.

Expecting your team to document a defect via a separate backlog item adds unnecessary work, slows the team down, and could lead to an adversarial relationship.

If you want to move testing up into the development process, adjust your documentation approach to meet the problem you’re trying to solve.

Thanks for reading

Thanks again for reading InsideProduct.

If you have any comments or questions about the newsletter, or there’s anything you’d like me to cover, let me know.

Talk to you next time,

Kent