How to make PRDs useful for internal products

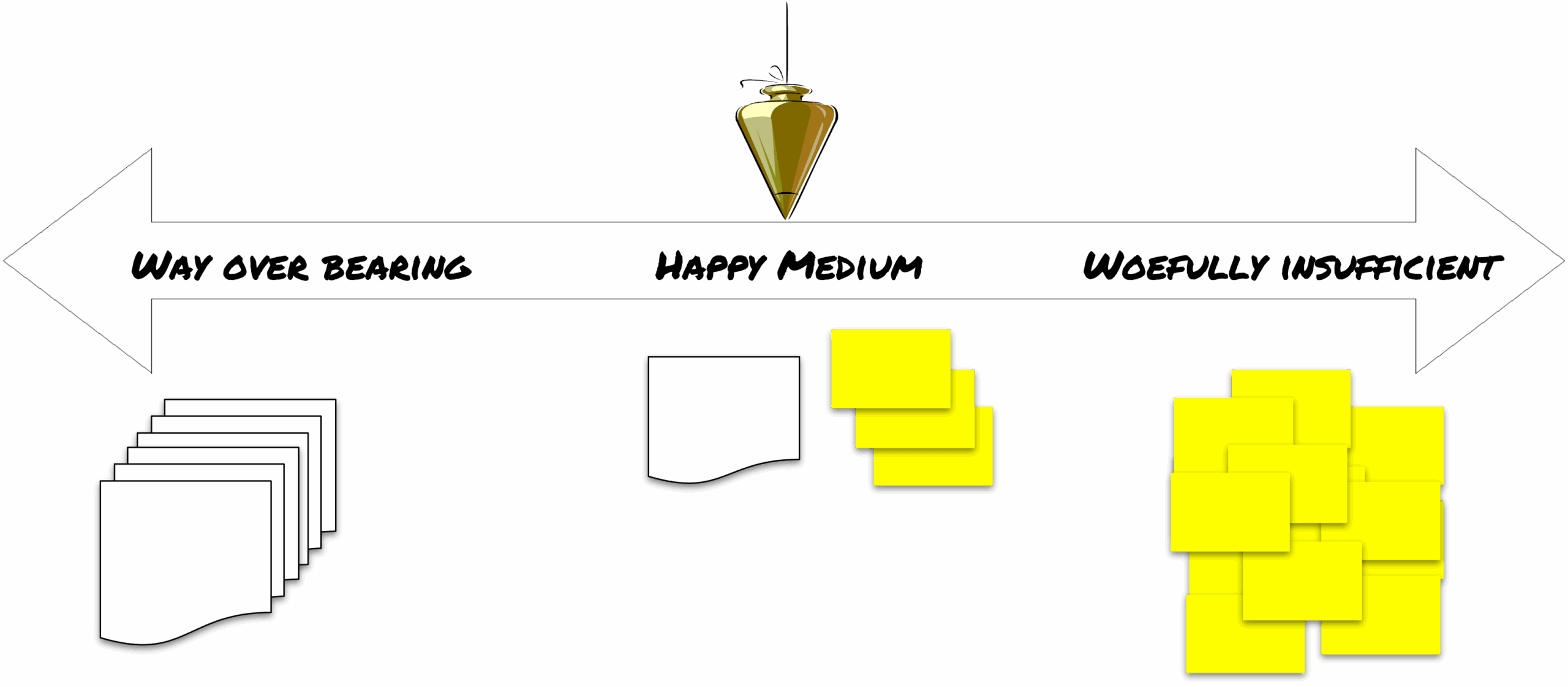

Over the course of my career, I’ve witnessed a few trends in software development. Many of these trends seem to take on the characteristics of a pendulum where practices swing from way over bearing to woefully insufficient. Both extremes lead to difficulties for teams which drives to eventually find a happy medium.

The documentation pendulum

Case in point is the documentation that teams use to describe what they want to build. The way over bearing end of the pendulum are extensive requirements documents, be they business requirements documents or Product Requirement Document (PRD).

There’s nothing more disheartening than pouring weeks of efforts to create an epic (pun intended?) requirements document only to see engineers derisively look at it for a few seconds before they figuratively, or literally, throw it in the trash.

The woefully insufficient end of the pendulum is a stack of index cards with disconnected user stories written on them. We have over zealous, and ill informed, agile coaches to thank for convincing teams to take the phrase “working software over comprehensive documentation” seriously and literally.

As a product team, we actually want to know what we’re trying to accomplish, so that we can build something that people will find useful.

Turns out there is a happy medium. You can collaborate on a PRD for your internal product to set context without completely describing the solution you want to build.

Here’s some things to consider if you want to take advantage of this happy medium approach to documentation.

PRDs provide context, not contracts

The primary purpose of a Product Requirements Document is to provide context.

Not to fully specify everything at the beginning.

Not to lock down every detail before discovery starts.

And definitely not to create a 30-page tome that no one will read.

Your PRD should clearly explain: Why are we building this, and what problem does it solve?

The specific requirements, the detailed user stories, the technical specifications emerge through collaboration.

They come from working with your engineers, your business stakeholders, and your actual users. The PRD starts that conversation; it doesn’t end it.

This is especially critical for internal products, where you’re often balancing competing stakeholder needs, legacy system constraints, and evolving business processes.

You can’t possibly know all the answers upfront. Pretending you do just wastes everyone’s time.

So remember:

-

A PRD is not a backlog. It is not a user story list, nor a technical design doc.

-

Context over content. The PRD should give just enough information to allow meaningful team discussions and prioritization.

-

Documentation is a starting point for collaboration, not a finished artifact.

Keep It Lean: The One Page One Hour Approach

If you spend days perfecting your PRD before sharing it with anyone, you’re doing it wrong. To make sure your PRD is the starting point for collaboration, check into the One Page One Hour pledge.

The pledge is simple: spend no more than one page and one hour working on any deliverable before sharing it with your colleagues.

The time you save isn’t just your own writing time. It’s also the time your team saves not having to read an excessively long document.

More importantly, you get feedback faster, which means you learn faster and iterate faster.

One Page One Hour works particularly well in the early stages of product work, when you’re still figuring out the problem space.

Instead of presenting at each other with polished documents, you collaborat with each other using rough drafts. The definition of “done” shifts from “is this impressive?” to “is this useful?”

And yes, one page can cover the essentials. You don’t need elaborate formatting or exhaustive detail.

You need clarity about the problem you’re solving and why it matters.

PRDs Don’t Need to Specify Every Requirement

Here’s a misconception that trips up a lot of product people: they think a PRD needs to contain all the requirements that might be relevant to the product.

It doesn’t.

A PRD is not a functional specification, backlog, or technical design document. Those artifacts serve different purposes and should exist separately.

Your PRD should include:

-

The problem you’re solving and why it matters to the business

-

Who experiences this problem and how it affects their work

-

What success looks like in measurable terms

-

What’s in scope for this effort (and just as importantly, what’s out of scope)

-

Key assumptions you’re making and any dependencies you’re aware of

That’s it. You can cover all of that in a single page when you’re just getting started.

The detailed requirements? Those get captured in your backlog as you work through discovery. They emerge from conversations with users, technical spike results, and prototype testing.

Trying to document them all upfront just creates waste—and often creates wrong documentation that then needs to be maintained or ignored.

How PRDs Evolve Through the Product Lifecycle

You’ll also find that the format and length of your PRD will vary based on where you’re at in the product lifecycle.

The PRD for a brand-new internal platform looks different from the PRD for an enhancement to an existing system.

Development Stage: The Problem Brief

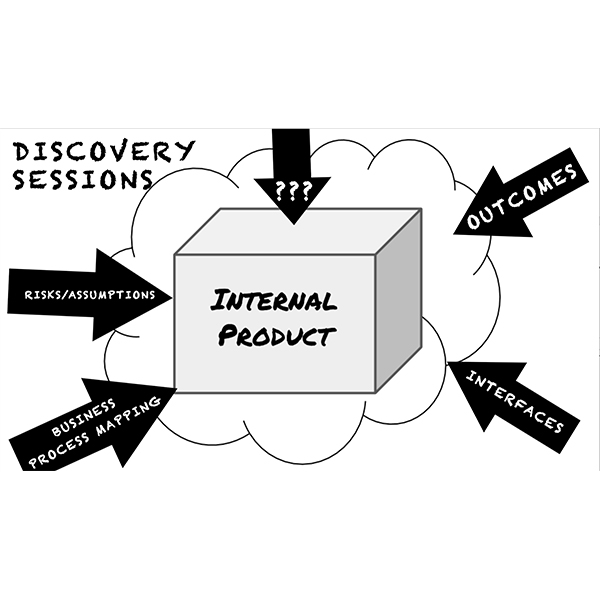

When you’re in the early stage and exploring whether to build a new internal tool or considering a major platform replacement your PRD is really a problem brief.

Format: One page, conversational tone, heavy on context

What to include:

-

Clear problem statement with supporting data

-

Who is affected and how often they encounter this problem

-

Current workarounds and their costs (time, money, frustration)

-

High-level business impact if the problem is solved

-

What you need to learn next

Example scenario: You’re exploring whether to build a custom inventory reconciliation tool. Your one-page brief explains that warehouse staff are spending 15 hours per week manually reconciling data between three systems, costing the business roughly $45,000 annually in labor. You estimate this problem affects 12 people across four locations.

This format works because you’re not committing to a solution yet. You’re building shared understanding about whether this problem is worth solving.

Introduction Stage: The Solution Outline

Once you validated the problem is worth solving and decided to move forward, you can expand your PRD to include solution direction without including an overly detailed specification.

Format: Two to three pages, structured sections, includes wireframes or workflow diagrams

What to add to your problem brief:

-

Proposed solution approach at a high level

-

Key user flows or scenarios

-

Success metrics and how you’ll measure them

-

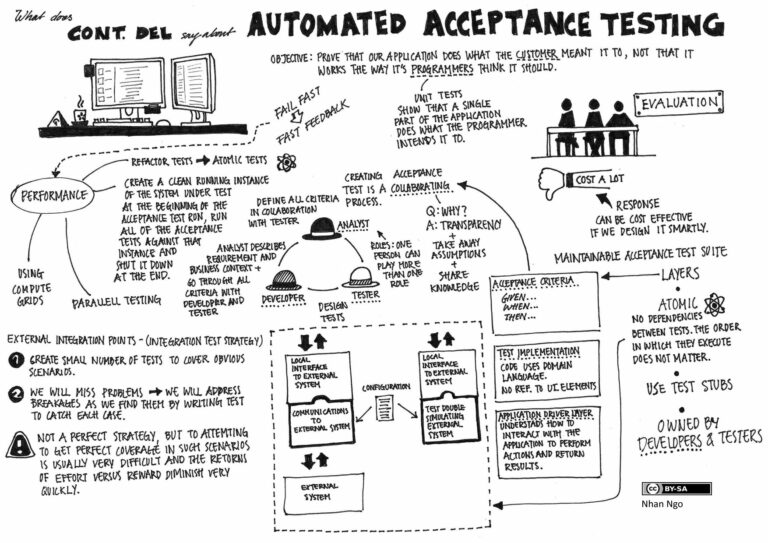

Dependencies and integration points

-

What you’re explicitly not doing in this release

-

Open questions that need answers during development

Example scenario: For that inventory reconciliation tool, you expand the PRD to outline a solution that:

-

pulls data from all three systems nightly

-

flags discrepancies above a threshold

-

surfaces them in a simple dashboard.

You may include a sketch of the dashboard, describe the three key workflows (initial setup, daily review, and exception handling), and note that automated resolution is explicitly out of scope for the first version.

You may also list open questions about data retention requirements and approval workflows.

This format works because the team has enough direction to start building, while leaving room for them to influence the technical approach and surface better solutions.

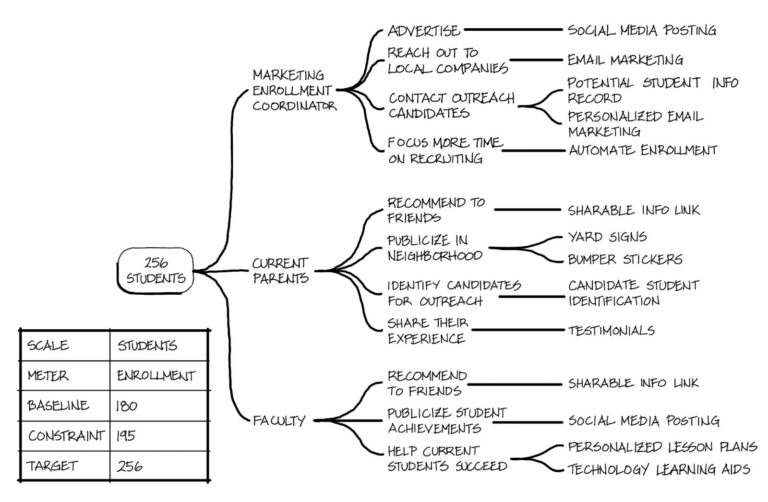

Example PRD for Development and Introduction

Maria Korteleva’s PRD Template provides a great example of a format you can use to create a PRD that you can gradually complete with your team as you move through the development and introduction stages.

This kind of targeted, context-rich PRD is far more actionable than an exhaustive specification. It provides just enough to align your team without bogging everyone down in too much detail.

Growth and Maturity Stages: The Enhancement Spec

When you work on an established internal product to add features, improve workflows, or address technical debt your PRD becomes more focused and tactical.

I’ve found it helpful to put some thought into how I structure the information I put into Epics in your favorite backlog management tool.

Format: One to two pages, specific and detailed on scope, lighter on context

What to include:

-

Brief context (since the product and its users are known)

-

Specific gap or improvement being addressed

-

Detailed acceptance criteria for the enhancement

-

Impact on existing functionality

-

Migration or communication plan if needed

-

Clear definition of done

Example scenario: Your inventory reconciliation tool has been running for six months. Users have requested the ability to bulk-resolve certain types of discrepancies.

You craft a “PRD” in the form of an epic description that explains this specific enhancement: add a checkbox interface to the dashboard that allows users to select multiple items and resolve them with a single action.

You include specific acceptance criteria (must support selection of up to 50 items, must require confirmation before resolving, must log each action individually) and note that this affects the existing resolution workflow. You specify that existing functionality remains unchanged.

This format works because everyone already understands the product and the problem space. You don’t need to rebuild that context—you just need to be specific about what’s changing.

Example PRD for Growth and Maturity

I’ve found the outline that Lenny Rachitsky described in his article A Three-Step Framework for Solving Problems a good way to structure epic descriptions.

The different sections lay out how to state a focused problem, validate with evidence, define success, and align on audience and vision before trying to design a solution.

Practical Tips for Internal Product PRDs

After working with various internal IT systems and operational platforms, here are a few things I’ve learned the hard way:

Start with the business impact. Internal product stakeholders care about efficiency gains, cost reduction, and risk mitigation. Lead with that. “This will save the accounting team 8 hours per week during month-end close” is more compelling than “This will improve data synchronization.”

Name the trade-offs explicitly. Internal products operate under real constraints such as limited budgets, small teams, and integration challenges. Be upfront about what you’re not doing and why. This prevents the endless scope creep that kills internal product initiatives.

Link to the money. I wrote about this in a previous piece, but it bears repeating. Connect your PRD to financial impact whenever possible. Whether it’s labor cost savings, reduced error rates, or faster cycle times, quantify the impact.

Keep your PRD where your team works. If your team lives in Confluence, put it there. If they’re in Notion or SharePoint or even a shared Google Doc, use that. The best PRD format is the one your team will actually read and reference.

Don’t bury the lede. Put the most important information first. If someone only reads the first paragraph, they should understand what problem you’re solving and why it matters.

When to Write (and Not Write) a PRD

Not every piece of work needs a PRD.

A PRD may be useful when:

-

You’re introducing a new product or major capability

-

Multiple teams need to coordinate on the work

-

There’s potential confusion about scope or direction

-

Stakeholders outside your immediate team need to understand what’s being built

-

You need to document decisions for future reference

Don’t write a PRD when:

-

You’re making a small, isolated change to existing functionality

-

The work is purely technical (refactoring, infrastructure, etc.)

-

The team already has complete shared understanding

-

You’re still in early exploration and haven’t validated the problem

Use your judgment. The goal is documentation with a purpose, not documentation for its own sake.

PRDs as a living tool, not a burden

The best PRD is one that helps your team build the right thing efficiently. It’s not about impressing stakeholders with comprehensive documentation. It’s not about covering yourself if something goes wrong. And it’s definitely not about satisfying some corporate requirement to “have a PRD.”

It’s about creating shared understanding.

When you approach PRDs as lightweight, evolving documents that provide context rather than comprehensive specifications, they become genuinely useful.

Your team spends less time writing and more time building. Stakeholders get the information they need without wading through pages of details. And you maintain the flexibility to learn and adapt as you work.

So the next time someone asks “Where’s the PRD?”, you can confidently share a single page that took you an hour to write. Because that’s all you need to get started.

Thanks for reading

Thanks again for reading InsideProduct.

If you have any comments or questions about the newsletter, or there’s anything you’d like me to cover, let me know.

Talk to you next time,

Kent