Who really does internal product management

When I decided InsideProduct should focus on the trials and tribulations that come from working on internal products, I figured I should probably try to get into the heads of the people most directly affected.

One group of those people are CIO’s those sometime members of the C- Suite who have struggled over the last ten years convincing their peers that they exist for more than providing tech support and spending millions of dollars migrating from SAP ECC to SAP S4/Hana.

So I’ve started paying attention to CIO Magazine and a recent article caught my attention because it tackled the project to product shift from the project management perspective. This excerpt stood out:

The biggest misconception about the project to product shift is you have to choose one over the other. Success requires both. Product managers own the vision, ensure alignment with business goals, and focus on long-term value creation. Project managers, on the other hand, ensure the right people do the right work in the right way to drive the intended business outcomes, maximizing the worth it factor and ROI.

The best results come when you have both groups playing to their strengths instead of trying to have one role do it all. The natural tension between setting the vision and executing it efficiently is where the magic happens. That push and pull is what keeps organizations moving forward at the right speed and focused on the outcomes.

I read that passage and pondered the description of what a product manager does versus what a project manager does. The descriptions aren’t wrong, but they put something into stark relief for internal products.

Product managers for internal products aren’t product managers

Many people who work on internal products and “own the vision, ensure alignment with business goals, and focus on long-term value creation” aren’t called product managers. They’re usually called Director or VP and are the leader of the business area that “owns” the process the internal product enables.

That also means they’re much more interested in the process they’re trying to enable than they are about the processes surrounding product management. In some respects that’s ok, because it means that they’ll be less likely to worry about if they’re doing product management the “right way”. They probably don’t even realize they’re doing product management.

That’s also the downside. They’ll focus more on their view of the process rather than doing proper discovery. It also means they probably won’t be as willing to make the tough decisions, or properly describe the solution with the team, let alone work with the team to craft a solution.

A brief history of product people

This situation existed before organizations wanted to adopt a product operating model. It started decades ago as IT departments tried to figure out what “the business” wanted and so established roles for that purpose. Voila – business analysts.

Then IT departments started adopting agile and the role and teams adopted the product owner role, because that’s what scrum said to do.

Except these product owners weren’t what Ken and Jeff had in mind when they created scrum. In fact, the initial paper describing scrum referred to product managers. They changed the name to product owner to signal a shift from someone writing up PRD’s and tossing them over the wall to someone actively stewarding the product and continuously collaborating with developers.

I should note here that Ken and Jeff worked in an external product setting. “The business” was actually people responsible for figuring out how to make money with their products.

They were product managers. And by inference, they should care about how the product is built, and thus they should spend a healthy amount of time with the people building the product.

Seen in that light, it may be understandable why Ken was aghast when he saw people who weren’t the ultimate decision makers inserted in between the decider and the product team. He referred to these folks as proxies, and even derisively compared these “proxies” to business analysts or requirements engineers.

I’m going to guess that when Ken shared those thoughts he hadn’t had a good experience with business analysts.

So who manages internal products?

I’d argue things look different in the world of internal products.

Those Directors and VPs who “own the vision, ensure alignment with business goals, and focus on long-term value creation” for an internal product won’t give up their day jobs so they can spend half their time in the product team room playing with sharpies and sticky notes.

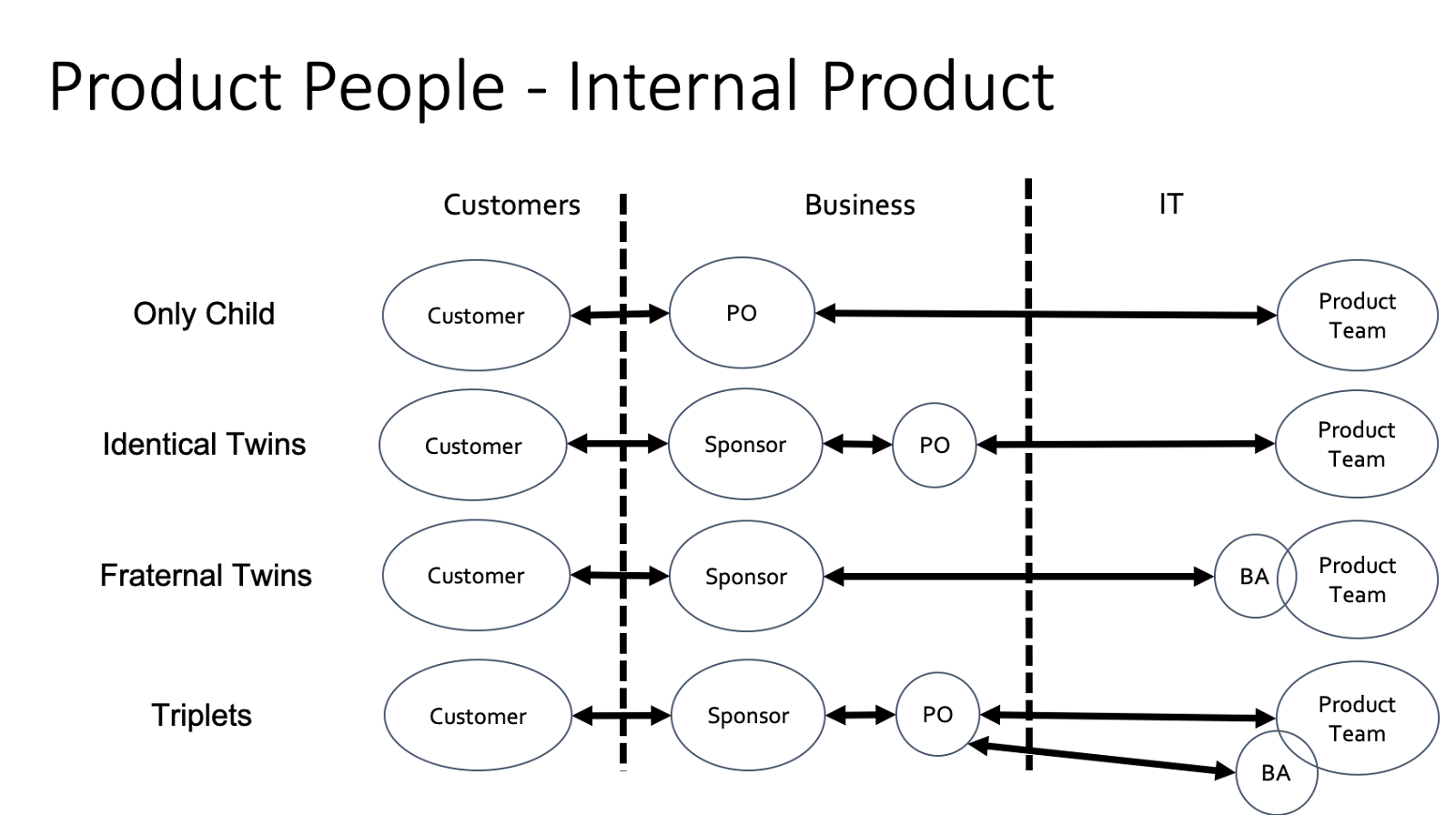

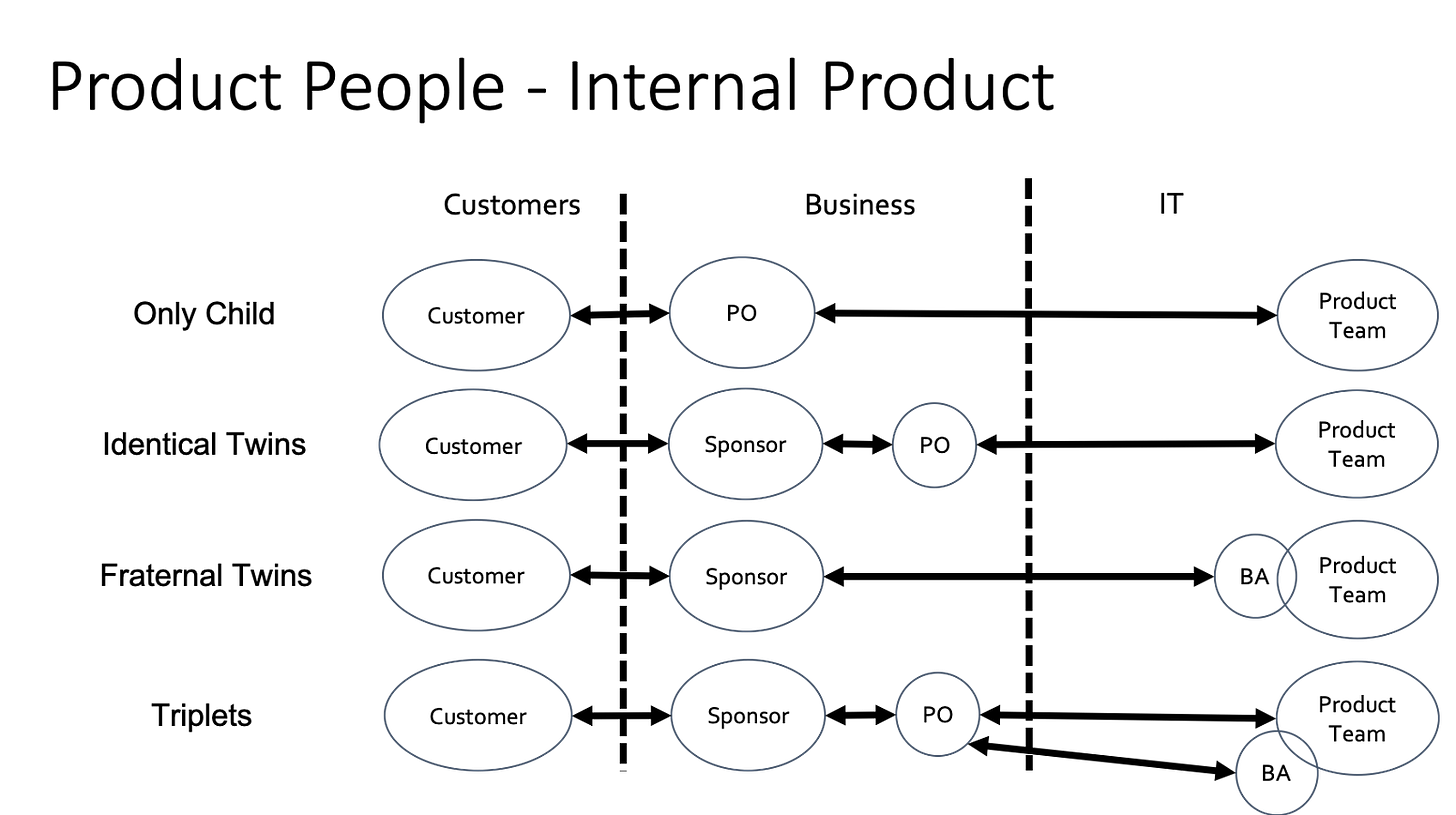

That’s why you have the Identical Twins or Fraternal Twins models for organizing product people shown below. By the way, the “Sponsor” term is a catch-all for “Director or VP”.

You’ll probably need somebody who can collaborate with the product team and make sure that the Director or VP is properly engaged to make the key decisions. Ideally that person will make most decisions on behalf of the Director and VP to keep things moving and make the best use of everyone’s time.

That’s what effective product ownership looks like in an internal product setting. And a key set of skills for that person are those they get from a background in business analysis.

An example of how this works

We used the Fraternal Twins model for the pricing app I worked on a few years ago. The main decision maker (who ironically held the official role of product owner) was a director of finance. He was the main decision maker because he owned the business process that used the pricing app.

My official role was delivery lead, which was originally envisioned as a cross between a scrum master and agile coach. It soon became apparent that the director of finance would not be the product owner that people expected. Not through any fault of his, but because he just didn’t have the time or experience to do that sort of work.

So I adopted a vast majority of typical product ownership responsibilities, leaving the director to focus on key decisions and provide air cover when necessary. Oh yeah, and his normal 60 hour a week job.

I fulfilled parts of product management and project management that CIO Magazine article described.

One context’s proxy is another context’s product owner

There are a few key points from all of this:

Product roles have different responsibilities in different situations. When deciding who does what in your situation, start with what needs to happen and figure out who has the capacity and ability to do the key things.

Product management still can apply to internal products, but it’s going to look different in some key ways from products for sale, and that’s ok.

Don’t expect a director or VP to be a product owner if they can’t commit the time to it. Instead have someone with the proper capacity and ability act as the product owner. Let the director make the key overarching decisions in a way that doesn’t make them an obstacle. In this context, this is not creating a proxy, it’s making smart use of everyone’s time and skills.

I’ll admit I’m using this post to think through these ideas, so I’d love to hear your thoughts on whether I’m totally off base or if some things hold true.

Thanks for reading

Thanks again for reading InsideProduct.

If you have any comments or questions about the newsletter, or there’s anything you’d like me to cover, let me know.

Talk to you next time,

Kent